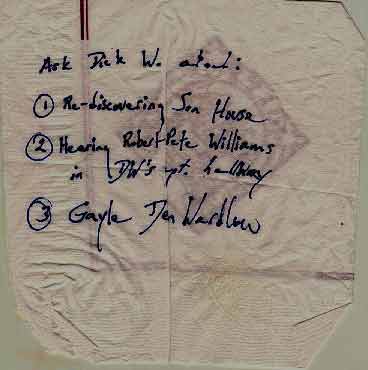

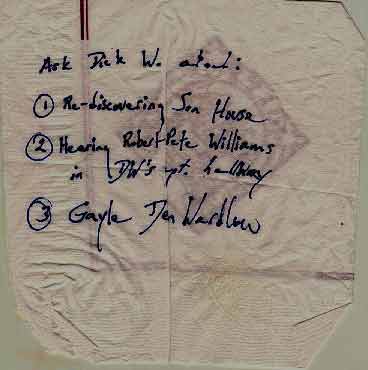

Dick Waterman

The summer of 1964: a racist crime wave scorched Mississippi, Wallace ran for president and activists went into

the rural south to register voters, and three Jewish kids in a yellow Volkswagen with New York plates

went to the Delta to look for Son House. Dick Waterman was one of them.

The previous year, Waterman had met "Mississippi" John Hurt at the Newport Folk Festival, then lined

up a week of concerts for Hurt in Boston. Waterman then began work with Booker White, and it was White who first

mentioned seeing Son House in Memphis. House, like a number of bluesmen, had been missing from the blues scene

for several decades. Also like other bluesmen, Houseās early recordings were beginning to see a revival of interest

among white audiences. In short, there was a market for Houseās work in 1964, and Waterman set out to find him.

On Sunday, June 24, 1964 Bruce Waterman first spoke to Son House in Rochester, where he had been living since retiring

from a railroad job. House agreed to play again, and Waterman agreed to find him venues. Houseās first concert

after his rediscovery was in October of 1964 at Antioch College. In 1965, A & R man John Hammonds signed House

to Columbia Records. |

(Bar napkin with questions for Dick provided by "Fast Eddie" Komara.) |

Watermanās success in getting Son House work and a contract with a major record label meant that artists began

to seek him out. Waterman started Avalon Productions, named for "Mississippi" John Hurtās home town,

and began to represent more rediscovered blues talent. One such artist was Robert "Pete" Williams.

Williams had been recorded by Harry Oster, Ph.D., who was at that time a professor at the University of Louisiana.

Oster had recorded "Folk Lyric," an album of prison spirituals, at Angola, Louisiana where Williams was

doing time. Williams served seven years at Angola, and was paroled in 1964 just weeks before he was invited to

play at the Newport Folk Festival. While in Newport, Williams stayed with Waterman.

Williams was an extremely superstitious man who did not read or write and had no way of contacting his family

in Louisiana while he was in Newport. While on stage Williamsā style was rough and bluesy, with a steady-driving

beat, but one morning Waterman heard him playing very differently. Williams was sitting in the stairwell playing

quiet, lyrical melodies on his guitar. When Waterman asked why he did not play in that style on stage, Williams

said he was, just talking to [my wife] Hattie Mae, telling the kids to do their homework and not to get worried,

I missed her and Iād be home soon.