|

|

|

The Marginalizing Intersection of Race, Gender and Class: Black

Women and Domestic Space

|

|

|

| For black women experiencing the tension between the pressure to work and the pressure to

marry and be a mother, performing their own household chores-in addition to working a low status job, such as domestic

service and laundry work-provided a way to bridge the two. |

|

|

Woman storeowner, Alabama. |

The majority of black women workers held such jobs, due to employers' preferences for white

women. Although many black women were qualified to hold clerical and sales positions, employers tended to prefer

filling the jobs with white women. Factory jobs were scarce as well. As a result, few black women worked in the

professions. Teachers comprised the largest group, followed by small numbers of nurses and midwives (Hunter 112).

For some black women, owning and operating their own businesses proved more lucrative than attempting to attain

work from a white employer. |

|

|

| When industrial jobs opened up in the north during the Migration, white women left their

domestic jobs for them, leaving the field open to black women, a shift that has numerous implications for the evolution

of American social norms and values during the Migration. Although black female migrants sought employment years

after Emancipation, the hierarchy imposed by slavery persisted in the different cultural values society attached

to black and white women. Black women did not necessarily choose to enter the domestic field; rather, among a sea

of jobs occupied by white women, the domestic arena was one tossed aside, left for black women to pick up, effectively

marginalizing the field as the black woman's sole alternative to unemployment. Hazel Carby discusses black women's

employment in capitalistic and patriarchal terms: "free women in US white patriarchy were exchanged in a system

that oppressed them [marriage], but white women inherited black women and menů.In a racist patriarchy, white men's

'need' for racially pure offspring positioned free and unfree women in incompatible, asymmetrical symbolic and

social spaces." As Cara Mertes notes, "In such a system, Black women are seen as expendable, and white

women are valued as priceless" (Mertes 69). |

Black maids with white child. |

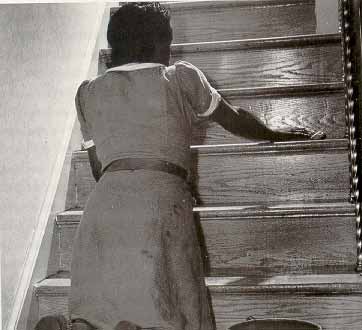

Maid cleaning stairs. |

|

|

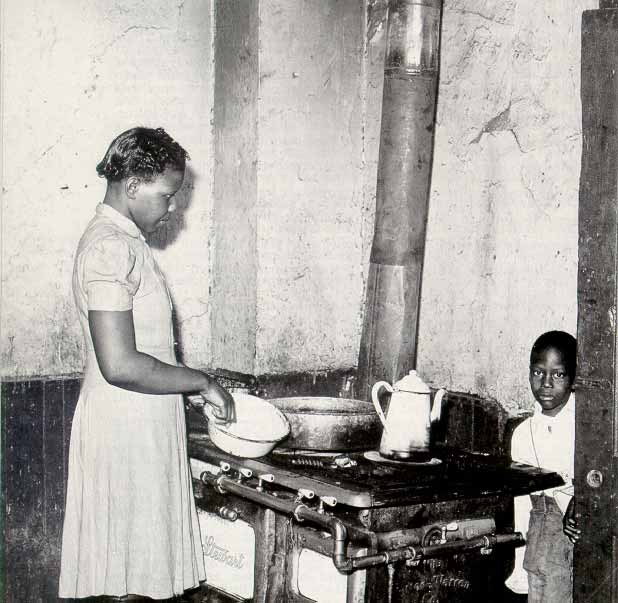

Mother in her own kitchenette.

|

This dichotomy further played itself out within the space of the white, middle class home,

where many black women worked as live-in domestics before the Civil War. Within this setting, social roles and

cultural expectations gained their foundation from emphasized oppositions between race and class. |

Domestic worker in a white family's kitchen.

|

|

|

|

|

![]()