|

|

|

Interview

Oliver Montgomery: From the Mill to the Union

|

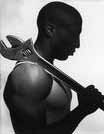

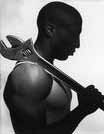

In the course of our research for this project, our group

had the privilege of interviewing Mr. Oliver  Montgomery-- formerly

of both the United Steel Workers of America in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

and the Youngstown Sheet and Tube Company of Youngstown, Ohio. Mr. Montgomery's

vocational experience places him in a uniquely qualified position to comment

on the importance of industry-- specifically as it relates to coal, steel,

and unions-- to the African American community. His father and grandfather

were both employed as miners in the South. His family pulled up and headed

to West Virginia's expanding mines to take advantage of the greater job

opportunities, from where they moved to Ohio where Mr. Montgomery, just

like his father and grandfather, found employment in the steel industry. Montgomery-- formerly

of both the United Steel Workers of America in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

and the Youngstown Sheet and Tube Company of Youngstown, Ohio. Mr. Montgomery's

vocational experience places him in a uniquely qualified position to comment

on the importance of industry-- specifically as it relates to coal, steel,

and unions-- to the African American community. His father and grandfather

were both employed as miners in the South. His family pulled up and headed

to West Virginia's expanding mines to take advantage of the greater job

opportunities, from where they moved to Ohio where Mr. Montgomery, just

like his father and grandfather, found employment in the steel industry. |

| At the Youngstown Sheet and Tube Company Mr. Montgomery took a position as an industrial brick-layer. He began

as an apprentice brick-layer in 1948. Though professionals and tradesmen, African-American workers at this time,

(nearly twenty years before the Civil Rights Act of 1964) found themselves disrespected, downtrodden, and more

often than not, trapped in dead-end low-level jobs. If, as in the case of Mr. Montgomery, one was able to learn

a skill and secure a stable position in the company, an African American worker may very well be cheated out of

a portion of his pay, or drastically underpaid as compared to a white man. African American workers did not enjoy

equal representation in the unions, and as a result, for many years they could not efficiently organize themselves

to petition for equal labor practice. |

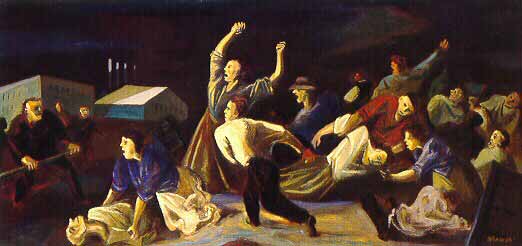

Youngstown was the third largest steel producing city in the

United States by the mid 1930's, behind Pittsburgh and Chicago. But while

the city enjoyed a certain modicum of prosperity as a result of the influx

of steel money, at the same time, the unfair labor practices of the steel

magnates plagued the city with unrest. As Pittsburgh endured violent strikes

at the close of

the nineteenth century, and the hills of West Virginia were reddened by

the blood of oppressed workers, so too was Youngstown beset with labor induced

strife. In 1917 and again in 1937 Youngstown mill workers and mill driven

officials fought in the streets of the city. The Steelworkers Organizing

Committee (SWOC) coordinated simultaneous strikes at Bethlehem, Republic,

National, and Inland Steel Companies as well as at the Youngstown Sheet

and Tube Company on May 26, 1937. Before the end of the strike, sixteen

lives were lost.(Painting:William Gropper: Depiction of 1917

Strike in Youngstown circa 1936) of

the nineteenth century, and the hills of West Virginia were reddened by

the blood of oppressed workers, so too was Youngstown beset with labor induced

strife. In 1917 and again in 1937 Youngstown mill workers and mill driven

officials fought in the streets of the city. The Steelworkers Organizing

Committee (SWOC) coordinated simultaneous strikes at Bethlehem, Republic,

National, and Inland Steel Companies as well as at the Youngstown Sheet

and Tube Company on May 26, 1937. Before the end of the strike, sixteen

lives were lost.(Painting:William Gropper: Depiction of 1917

Strike in Youngstown circa 1936) |

The unions were the very foundation of Youngstown itself and

thousands of workers, because of the color of their skin, found themselves

disenfranchised and without a voice. Even in this situation, African American

workers found ways to make their presence known. The United Steel Workers

of America (USWA), the union proper, was organized in 1936. Steel workers

organized a committee and then teamed up with the Congress of Industrial

Organizations under John L. Lewis. They moved to organize the industrial

trades, since the American Federation of Labor (AFL) was, at the time, restricted

to craft workers. A complete industrial union was only to be found with

the CIO. The CIO started to try to organize industries and crafts together

in 1935-36. In 1942 the USWA became recognized. But no Blacks or women could

join any of these  organizations. According to Mr. Montgomery, by the time

of the civil rights movement, however, a "few blacks had broken into

top positions" in the USWA. For many years the African-American workers

had been forced to meet in secret. Youngstown was one of the "key corners

of the union" and elements within the union were frightened by the

prospect of African Americans (who in some mills held over fifty percent

of the positions) organizing themselves. Those taking the lead, like Mr.

Montgomery, were under constant threat and were often fired. However the

seeds were sown and the roots of organization were entrenched enough that

African American workers could get certain one's rehired. If African Americans

were unable to orchestrate the placement of a candidate of their own in

a certain position, they utilized traditional political machine tactics

to place a given white candidate in a position in exchange for certain concessions

toward equality. Organized work slow-downs, stoppages, and sit-downs on

the job caught the attention of both the mills and the union. Some organizers,

followed the lead of pioneer A. Philip Randolph organizations. According to Mr. Montgomery, by the time

of the civil rights movement, however, a "few blacks had broken into

top positions" in the USWA. For many years the African-American workers

had been forced to meet in secret. Youngstown was one of the "key corners

of the union" and elements within the union were frightened by the

prospect of African Americans (who in some mills held over fifty percent

of the positions) organizing themselves. Those taking the lead, like Mr.

Montgomery, were under constant threat and were often fired. However the

seeds were sown and the roots of organization were entrenched enough that

African American workers could get certain one's rehired. If African Americans

were unable to orchestrate the placement of a candidate of their own in

a certain position, they utilized traditional political machine tactics

to place a given white candidate in a position in exchange for certain concessions

toward equality. Organized work slow-downs, stoppages, and sit-downs on

the job caught the attention of both the mills and the union. Some organizers,

followed the lead of pioneer A. Philip Randolph  and the Negro American Labor Coalition (NALC) organized

and "declared war on the union" itself . By virtue of this organized

effort the newly elected president of the union, I.W. Abel was forced to

take African-American worker's demands into consideration. and the Negro American Labor Coalition (NALC) organized

and "declared war on the union" itself . By virtue of this organized

effort the newly elected president of the union, I.W. Abel was forced to

take African-American worker's demands into consideration.  The workers demanded more blacks in higher paid positions,

better jobs, and representation at the union headquarters in Pittsburgh.

Abel was forced to form a civil-rights committee, and take action by appointing

African-Americans to his staff, such as Mr. Montgomery. Mr. Abel had no

intentions of being displaced as was his hard-hearted predecessor, Mr. MacDonald. The workers demanded more blacks in higher paid positions,

better jobs, and representation at the union headquarters in Pittsburgh.

Abel was forced to form a civil-rights committee, and take action by appointing

African-Americans to his staff, such as Mr. Montgomery. Mr. Abel had no

intentions of being displaced as was his hard-hearted predecessor, Mr. MacDonald.

(Pictures here from personal collection of Oliver Montgomery.) |

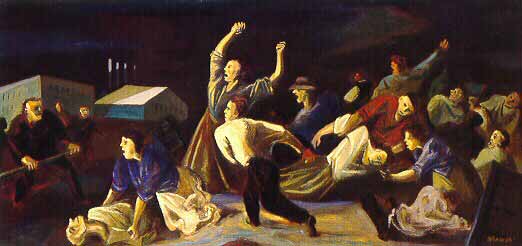

Though it seemed for a time in the late 1970's and early 1980's

that some strides were being made as concerned racial equality, the worst,

in a way, was yet to come. There was a "revolution in steel" as

an industry. What that meant was that foreign competition, a sick domestic

economy, environmental regulations, and mechanization all contributed to

the downfall of the industry. With cheap German and Japanese steel flooding

the market, American steel companies were forced to articulate a response

in some way. By bringing in new technology and

cutting down on the labor force, the companies sought to stay competitive. The turmoil in the industry attracted

outside business interests. The steel industry revamped its procedures, changing from the older more traditional

integrated steel mills (from start [ore] to finish [bars, tubes, and sheets]) to "higly efficient ultra modern"

mills, or "mini-mills" which specialize in making only a particular sort of specific finished steel product.

The Youngstown Sheet and Tube Company was taken over by Steamship Lydes, and then by Jones and Laughlin. Lydes

exemplified the "cartel" leverage buyout corporation. Knowing nothing of the steel business (except of

money to be gained in exploiting debt to equity ratios), and investing nothing in it; Lydes ran Youngstown Sheet

and Tubing into the ground and left it for dead. The revolution in the industry had many such casualties and Youngstown

is only one city. (To the right: A now-defunct furnace of the Youngstown Sheet & Tubing Company) |

| Mr. Montgomery retired in 1989. |

|

|

|

NEXT

|

of

the nineteenth century, and the hills of West Virginia were reddened by

the blood of oppressed workers, so too was Youngstown beset with labor induced

strife. In 1917 and again in 1937 Youngstown mill workers and mill driven

officials fought in the streets of the city. The Steelworkers Organizing

Committee (SWOC) coordinated simultaneous strikes at Bethlehem, Republic,

National, and Inland Steel Companies as well as at the Youngstown Sheet

and Tube Company on May 26, 1937. Before the end of the strike, sixteen

lives were lost.(Painting:William Gropper: Depiction of 1917

Strike in Youngstown circa 1936)

of

the nineteenth century, and the hills of West Virginia were reddened by

the blood of oppressed workers, so too was Youngstown beset with labor induced

strife. In 1917 and again in 1937 Youngstown mill workers and mill driven

officials fought in the streets of the city. The Steelworkers Organizing

Committee (SWOC) coordinated simultaneous strikes at Bethlehem, Republic,

National, and Inland Steel Companies as well as at the Youngstown Sheet

and Tube Company on May 26, 1937. Before the end of the strike, sixteen

lives were lost.(Painting:William Gropper: Depiction of 1917

Strike in Youngstown circa 1936)