|

|

|

INTERVIEW:

RAY HENDERSON

|

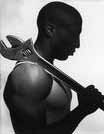

Raymond Henderson became well-known during his eighteen

years at the Dusquene steel mill in Pittsburgh. A self-described "hell

raiser," Ray was one of the few African Americans to break the racial

barrier in hiring practices at the mill. Refusing to be placated with his

own success, he determined to make similar achievements possible for other

Black workers. He challenged the union and steel company to break down racial

prejudice, both through his work on the grievance committee and his involvement

in the civil rights movement. other

Black workers. He challenged the union and steel company to break down racial

prejudice, both through his work on the grievance committee and his involvement

in the civil rights movement.

His work was not in vain: the Consent Decree of 1974 granted African Americans greater access to higher jobs and

equal pay in the steel industry. This success was short-lived, however. The U. S. Steel industry collapsed in the1980s,

plunging thousands of men and women into unemployment or early retirement.

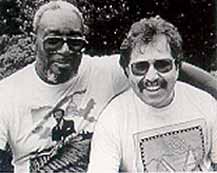

Determined to tell this story of victory gained and lost, Ray contacted his friend, filmmaker Tony Buba. Working

together, they made Struggles in Steel, a documentary containing the testimonies of African American steelworkers

from both the south and north.

Here is Ray's story. |

| |

|

|

| I was hired in a department where they never hired a Black for twenty years. I couldn't figure it out. What's the

big deal? Everybody here works hard; its hard labor. That kind of struck me as funny. I read my union contract

and realized there was a difference between how Black and white laborers were treated. Why was I getting class

two [pay] while [a white] guy was getting class three [for the same job]? I said, ‘This isn't right. I should be

getting the same as he is over there.' We're both doing the same kind of work. We were digging ditches. What made

his ditch digging any better than mine? That's what got me involved in the union. I started looking at those lines

of progression [systems of promotion] they stuck African Americans in, such bad ones that African Americans almost

never got above a class four or class five job. |

| |

|

|

There were no Blacks in trades and crafts. None. I mean, for

a Black to get a job laying bricks was like committing a sin.  Let

alone being a carpenter. Not even a painter. And a welder - you've got to

be kidding! It just didn't happen. I fought that for a long time. I had

to fight to get the inspector's job. It was class eleven. They didn't train

me; they gave me a book that I had to read and learn exactly what to do. Let

alone being a carpenter. Not even a painter. And a welder - you've got to

be kidding! It just didn't happen. I fought that for a long time. I had

to fight to get the inspector's job. It was class eleven. They didn't train

me; they gave me a book that I had to read and learn exactly what to do.

I was a grievance man [with the mill grievance committee]. I was still in the union. The union wasn't really a

receptive place for African Americans. Always there were one or two men in union offices, but they couldn't do

much. Never could be president or trustee of the grievance committee. Those [positions] had the ultimate authority.

At the international level [of the union] there were no Blacks until we raised a bunch of sand. Without enough

representation, we didn't have enough impact to get minorities some kind of justice. |

| |

|

|

We were 100% in support of the Consent Decree, [but it didn't

get us into all jobs]. Some of the higher paying sections of the plants

turned all Black real fast, but there were still no bricklayers, no carpenters,

not one electrician - even after the  Consent

Decree came into full play. All that was supposed to change, but it didn't.

The [industry] just wouldn't do it. They still found ways to hold African

Americans back. Consent

Decree came into full play. All that was supposed to change, but it didn't.

The [industry] just wouldn't do it. They still found ways to hold African

Americans back.

The Consent Decree was also supposed to pay Black steelworkers for the years of discrimination. And we got payed.

One guy worked thirty years; he got $900. He didn't take it. If you're deprived of thirty-five cents an hour, five

days a week, for thirty years, how much money did you lose? |

| |

|

|

On

the back of the check they had a contract. Its not just that you would sign

off that you forgave them for past discrimination, but that you couldn't

sue them for any future discrimination. There were a lot of guys that never

signed those checks - just tore them up. They were truly insulted by it.

The union played a role in that. They knew what they were doing [by not

protecting us equally]. I've always been bitter about that even though I

like the union: it gives you more flexibility to get the things you want.

I'm a union man, still. On

the back of the check they had a contract. Its not just that you would sign

off that you forgave them for past discrimination, but that you couldn't

sue them for any future discrimination. There were a lot of guys that never

signed those checks - just tore them up. They were truly insulted by it.

The union played a role in that. They knew what they were doing [by not

protecting us equally]. I've always been bitter about that even though I

like the union: it gives you more flexibility to get the things you want.

I'm a union man, still. |

|

|

|

NEXT

|

| |

|

|

Consent

Decree came into full play. All that was supposed to change, but it didn't.

The [industry] just wouldn't do it. They still found ways to hold African

Americans back.

Consent

Decree came into full play. All that was supposed to change, but it didn't.

The [industry] just wouldn't do it. They still found ways to hold African

Americans back.