|

|

| |

STEEL UNIONISM

|

|

The

spirit of inclusion is integral to unionism. United together, workers wield

greater strength than when standing alone. Yet despite the obvious benefits

of an inclusive policy, steel unions largely excluded African Americans

until the 1930s. Promise of greater worker strength could not compete with

white workers' prejudice. Steel companies exploited this hatred: they recruited

Black workers to break union strikes precisely because of the union's racist

politics. Blacks were safe to employ because their defection to the union

was impossible. Nor did African Americans want to join: the strikes were

their means to employment. Ironically, union exclusion eased African American

entry into steel. The

spirit of inclusion is integral to unionism. United together, workers wield

greater strength than when standing alone. Yet despite the obvious benefits

of an inclusive policy, steel unions largely excluded African Americans

until the 1930s. Promise of greater worker strength could not compete with

white workers' prejudice. Steel companies exploited this hatred: they recruited

Black workers to break union strikes precisely because of the union's racist

politics. Blacks were safe to employ because their defection to the union

was impossible. Nor did African Americans want to join: the strikes were

their means to employment. Ironically, union exclusion eased African American

entry into steel. |

| |

| SWOC enjoyed limited success; it convinced several major steel companies to increase wages and vacation time, establish

committees to hear workers' grievances, and install a "non-racist" system of seniority. Yet these dictums

on paper translated into few gains for Black workers in practice. Segregation persisted, confining African Americans

to the hazardous and low-paying "Negro jobs." Seniority rules, in relying on the steel company's assessment

of the worker's "ability, skill, and efficiency," allowed room for discrimination. And despite SWOC's

pledge to end racism among its members, African Americans were still subject to hostility from their co-workers. |

| |

|

Yet African Americans needed a voice in steel. Still fired in disproportionate numbers and confined to the lowest

paying positions, Black workers fared especially poorly in the Depression of the 1930s. Desperate to find relief,

they turned to the unionism of the Steelworkers Organizing Committee (SWOC). This group, along with its parent

organization, the Congress of Industrial Organization (CIO), determined to break the cycle of racial antagonism

that contributed to the defeat of the 1919 strike. SWOC was frustrated by the previous union's refusal pursue African

American recruitment. It formed in 1936 with the pledge to "promote the interests of all steel employees regardless

of craft and degree of skill, and to destroy discrimination based on color, both in the mills and within its own

rank and file" (Dickerson, 135). SWOC converted thousands of African Americans to unionism, earning the approval

of the Urban League, A. Philip Randolph, leader of both the Pullman Porter union and the National Negro Congress

(NNC), and some members of the Black press. The opportunity for union inclusion prompted one editor of the Pittsburgh

Courier to state, "[For] Negro labor [to] avoid the responsibility and opportunity which is now in its

grasp is criminal" (Dickerson, 138). |

| |

| Despite their claims, SWOC still did not offer Black workers equal "responsibility and opportunity."

In an interview conducted in January 2000, former Birmingham steelworker Virgil Pearson told us, "You'd

say 'Yes sir' or 'No Sir.' That's all you'd say if you were Black like me, or you'd be out of there."

SWOC appointed its first Black representative in 1948, yet his influence was extremely limited. Virgil said, "Yeah,

they thought it would look good from the outside but they wouldn't let him in the executive commitee. He was just

there for show." |

| |

|

|

| African Americans were drawn to SWOC's promises of racial equality in wages, union protection, and opportunities

for advancement. Yet not all were converted. Some remained skeptical of SWOC's purported non-discriminatory politics,

while others feared for their jobs - and with good reason. Although steel companies promised to fire anyone who

joined SWOC, they reserved their most serious threats for their Black workers. Steel agents accosted Black workers'

wives in some Pittsburgh mill towns, warning them "to keep their husbands out of the union if they wanted

them to remain employed (Dickerson, 143). Realizing the potential power of an integrated union, steel companies

determined to make this impossible. |

| |

|

SWOC enjoyed limited success; it convinced several major steel companies to increase wages and vacation time, establish

committees to hear workers' grievances, and install a "non-racist" system of seniority. Yet these dictums

on paper translated into few gains for Black workers in practice. Segregation persisted, confining African Americans

to the hazardous and low-paying "Negro jobs." Seniority rules, in relying on the steel company's assessment

of the worker's "ability, skill, and efficiency," allowed room for discrimination. And despite SWOC's

pledge to end racism among its members, African Americans were still subject to hostility from their co-workers. |

| |

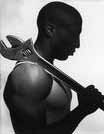

Despite federal support for racial equality in the workplace

in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Black workers saw few changes until the

era of civil rights in the 1960s. Borrowing the tactics of picketing, marches,

and boycotts from the movement, African Americans steelworkers protested

the racism still rampant in the industry. U. S. Steel attempted to disprove

the  legitimacy

of their grievances through a series of articles and advertisements depicting

Black workers in high power, high paying positions. Yet these stories failed

to depict the reality of the majority of Black workers - one of low pay,

the heaviest labor, and no chance for real improvement. legitimacy

of their grievances through a series of articles and advertisements depicting

Black workers in high power, high paying positions. Yet these stories failed

to depict the reality of the majority of Black workers - one of low pay,

the heaviest labor, and no chance for real improvement.

Federal action for civil rights translated into some gains for African American workers. Title VII of the 1964

Civil Rights Act established the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), an agency designed to pursue legal

action against racism by both companies and unions. Despite the formation of the EEOC and the insertion of a non-discrimination

clause into union legislation in 1962, the industry's progress against racism was limited in the 1960's. Although

they comprised 7% of the industry, by the end of the decade Black workers held only .6% of white-collar jobs and

3.1% of skilled jobs. |

| |

| The federal government took steps to remedy the dreadful inequality in steel industry in the 1970s. The Departments

of Labor and Justice, in conjunction with the EEOC, filed suit against nine steel companies and U. S. Steelworkers

of America, the national union. This suit resulted in the 1974 Consent Decree, a series of agreements designed

to end racial discrimination in the hiring and promotion of workers. Black steelworkers finally gained some kind

of equality of opportunity in 1974, but their victory was short-lived. The U. S. steel industry fell into severe

decline in the 1980s, plunging workers of all skin colors into unemployment. |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

NEXT

|

|

|

|