|

|

||

|

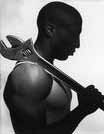

STEEL |

||

| The steel industry provided job opportunities for African Americans in both Birmingham and Pittsburgh. Lured by the potential for higher pay, many left the fields for the mill. Opportunity did not translate to equal access for African Americans, however. Racial discrimination was as rampant in the workplace as on the streets. Determined to uphold the economic structure that favored native whites, mill officials hired African Americans only as a last resort: when wartime need for steel demanded a massive workforce, or when the all-white unions went on strike. In both cases, companies actively recruited southern Blacks to migrate to steel centers. | ||

|

|

||

| Through newspaper ads and personal visits by labor agents, steel companies enticed African Americans with the promise of higher wages, opportunities for travel, and the excitement of change. Their campaigns were successful enough to decimate the workforce of the southern agricultural industry. With the viability of their economies at stake, Alabama, Arkansas, and Mississippi enacted legislation to halt the outflow of labor. They cracked down on the labor agents, both through police intimidation and the institution of high fees for recruitment licenses. Forced to drop their campaign of recruitment in person, the steel companies tried one in word: using names of family and friends given to them by African Americans already settled at the steel mills, labor agents solicited new workers through letters. This, coupled with advertisements placed in national African American newspapers such as the Pittsburgh Courier, inspired many to make the move to steel. | ||

|

|

The world they found was far from the one promised. Limited to the most dangerous jobs in the worst conditions,

African Americans found the mills rampant with racism. The steel companies used color as a weapon, purposefully

creating a tense environment to counteract worker solidarity and power. They employed Black workers as strikebreakers,

helping to defeat the great steel strike of 1919. Seen by many as traitors to a union that refused them membership,

African Americans worked in an atmosphere rife with hostility. Many African Americans refused to tolerate such conditions, choosing instead to try other mills or leave steel altogether. Unwilling to continue the hassle of constant recruitment, the steel companies attempted to halt the high turnover of African American workers by implementing welfare capitalism. Intended to bolster "loyalty, cooperation, and contentment," welfare capitalism came in several forms: steel giant Andrew Carnegie donated libraries to nearly every one of his steel towns, and the mills themselves offered segregated film showings, swimming pools, and baseball teams. |

|

| The northern steel companies also attempted to improve the dreadful housing availible to the Black workers. On the advice of the Pittsburgh Urban League, an organization dedicated to helping African Americans newly arrived in the city, the steel companies hired Black social service officers to work in the welfare program. Although these social service officers encouraged the companies to provide better conditions for African Americans in both home and work, their influence in the latter was severely limited. Black workers continued to suffer injustice both in and outside the mill walls. |

|

|