|

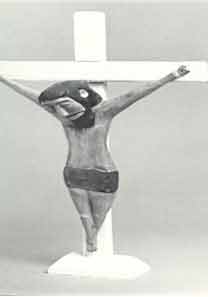

George Williams, Crucifixion, 1985, from Baking in the Sun: Visionary Images from the South |

Among the three encompassing categories of African American religion (Baptist, Methodist and Pentecostal), several underlying themes stand out. A fundamental belief is rooted in the sacred cosmos, with different religious idols, objects and figures at its center, depending on the specific denomination and church; the importance of the individual's relationship with God and Jesus Christ; the symbolic importance given to the word freedom; and most importantly, the role of the church as a center for worship, family, education, social and political life in the community. Between 1915 and 1950, Chicago underwent two main periods of phenomenal growth as African Americans from the Delta region of Mississippi migrated north. In both periods, labor, increased wages and better living helped to convince southerners to make the journey. The promises of labor agents and the propaganda of the Chicago Defender (which published horror stories of lynching in the south while glamorizing the north) eventually convinced people to stop thinking about migrating, and to take the first step-- by boarding the train. |

No single cause proves solely responsible for migration. However, in the Delta, such a large scale migration would not have been imaginable without the active participation of the church. Although southern ministers often discouraged congregation members from abandoning their roots, the appeal of a better life strongly affected many church leaders. Church deacons would help spread information of the migration, and Chicago's myriad possibilities, throughout the South. Without those church deacons sending their congregations north, the Defender would not have had letters to publish, flaunting opportunities in Chicago. The church served as the matrix connecting potential migrants with labor agents, who often worked through the deacon to reach the congregation, and the Defender.

| "As soon as the conductor said, ╬Chicago!' everybody got off, didn't know where they were at, didn't care," Reverend John Parker explains, originally from Meridian, Mississippi. "They came with burlap bags, cardboard boxes tied up with strings, pillowcases and sheets tied with belts. And everybody had a shoebox full of food." Expecting the streets to be paved with all of the sophistication associated with urban living, southern migrants soon discovered they still had to deal with racism, violence and poverty. Reverend Parker, who migrated north for the first time in 1942, remembers "seven or eight families living together in one house." |

|

In the bustle of bright lights and crowded streets, churches offered a sense of relief and community to displaced migrants. When reality became stifling, they could find refuge in churches such as Quinn Chapel A.M.E., Olivet Baptist Church, storefronts, and even the back rooms of private homes belonging to selected congregation members. Whereas in Meridian, Mississippi, "everyone went to the same church," African Americans in Chicago attended various churches, according to denomination, ritual and community.

Church Familiar Setting During Confusing Times

Despite tensions between different denominations, elite and rural congregations,

old settlers and new, the church provided peace and comfort to its members. Faith was never limited, and it was

just as prominent in the south. William Beauford, a member of the Springfield Missionary Baptist Church in Oxford,

explains:

|

William Beuford and son |

Church was the only thing black people had that they could call their own. . without the church we couldn't survive. . . [it's] like driving an automobile. You go to the station and fill up your automobile, and once you do that, you're ready for more mileage. During the week, you get empty again, but on Sunday, you go refuel for the next week. |

Standing in the kitchen area of University Pizza, his son's shop, Beauford talks with his hands. Fingers the size of sausages, he folds his hands, uses them to illustrate a steeple, waves them in the air and motions toward his heart whenever he speaks about his congregation:

A real church becomes a family . . . When one member is down, the

church is

down . . . [People think] the building is the church. But the church is in you, a

part of you. You have the church in you.

Whether the congregation is Baptist or African Methodist Episcopal, church provides a

place for both communal worship and individual freedom with God. Among the desolate fields, gray winter skies,

timber mills, abandoned stores and junk yards, churches also provide a space where memories of the past are fused

with present and future hopes. The Mound Bayou African Methodist Episcopal Church is bound to its history, as are

its congregation members every Sunday morning. Perhaps more than any other social institution, the church is crucial

to the preservation of African American history. Music fosters memory, and in every hymn, a different layer is

added to the collective memory of African Americans. Spirituality in Africa, the Middle Passage, slavery, the conversion

to Christianity, the Civil War and Reconstruction, segregation and migration÷ such histories live on within the

church, its congregation and music, despite the passage of time and changes in space.

Profile of Mound Bayou A.M.E. Church

The Mound Bayou A.M.E. Church, founded by thirteen ex-slaves in 1895, owes its life to the vision of the first settlers who wanted to create a legacy in the midst of a swampy terrain (now Highway 61 South). Since the beginning of the century, the town of Mound Bayou has fostered the first Wonderbread factory, a Coca-Cola factory, banks, stores, oil mills, gins and restaurants. Mrs. Mamie Myers remembers a time when Mound Bayou had an ice cream shop and picture shows. Recently, however, the town of Mound Bayou has been emptying out since people are moving north for opportunity. With shops closing, a lack of resources, school funds and employment, the land is haunted by its past problems. Except for teaching, preaching or government employment, most people work the fields or mills. Driving into Mound Bayou, the land is barren and flat, apparently unpopulated. However, inside the church is another story. The children's rhyme, "Here's the church/ Here's the steeple/ Open it up/ And see all the people," immediately comes to mind. In Mound Bayou, Mississippi, everyone and their grandmother (literally) goes to church. People seem to appear from out of the woodwork; such is the transformation from a barren landscape to a warm, spiritual, family and social atmosphere found within the church.

During our visit to Mound Bayou A.M.E. Church, we met and talked with Reverend Fred D. Raggs and members of the congregation, including Mr. C. Preston Holmes, Mrs. Pauline Holmes and Mamie Myers. Without their stories, our study of the black Methodist church in the Delta would be incomplete. Mrs. Pauline Holmes, whose father organized the first meeting of NAACP in their area, explained the functions of the church as a community center and "reaching out" organization. The church has been involved in such projects as building a local hospital, serving as voting registration centers, community fund-raising, and hosting various organizations from the NAACP to the American Legion Organization and even the Boy Scouts. Recent projects within the church have included educational programs for children and young adults, such as Bible Bees, Bingo and Quizzes. Also, the church serves as a place for social gathering with events like the African Heritage Luncheon, fashion shows, square-dancing and gospel concerts.

|

The ladies of Bethel A.M.E Church in Mound Bayou, Mississippi. |

Sacred Space by

Tom Rankin

Sacred Space by

Tom Rankin