THE SOUTHERN CHURCH

|

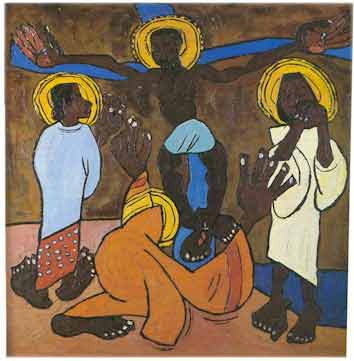

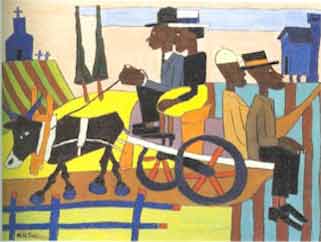

Tongues Archibald J. Motley Collection c. 1929 |

Religion played a central role in the lives of African Americans living in the Delta. More than any other social institution, the church played a crucial role in the spiritual realm of black Deltans as well as gave them a means to build networks that strengthened communal ties and legitimized personal desires. African Americans' Christianity, while assuming a vital role in the turbulent and troubling conditions of the South, posed many ideological and practical problems in the wake of their mass exodus. |

Origins of African American Christianity in the Delta

In the eighteenth century, as Christianity spread throughout North American slave

societies, white planters used Christianity to justify African Americans' debased status. Planters frequently attended

church with their slaves, forcing them to listen to ministers misconstrue Biblical teachings while perpetuating

the notion of the afterworld as a place of salvation only achieved through unquestioned subservience. Planters

efforts, however, were only partially successful. Not only did slaves interpet Christianity for themselves, they

imbued it with West African ideas and behaviors. Transformed, it became an instrument for African American identity

and creativity, as well as an outlet for collective expression.

Development of the Independent Church

Emancipation produced a number of changes in the structure and function of African

American Christianity. Previously Christianity had fallen the surveillance of whites. Freedom allowed blacks' the

opportunity to develop a separate and autonomous church. During Reconstruction, African Americans' saw the formation

and legitimization of separate churches as a crucial step in their integration and acceptance within southern culture.

With the end of Reconstruction, and the subsequent hardening of racial barriers, black churches increasingly became

a sanctuary against widespread white racism.

|

As racial conditions worsened, blacks sought to protect their churches from white control or influence. While blacks in the Delta lost hope of securing political power or economic security, the church loomed as an avenue toward personal fulfillment and societal betterment, while affirming their personal protection and hope. The church became an "all comprehending institution" within African American rural communities, filling many of the holes either withheld or simply ignored by whites. Many churches devoted much of their energy to providing their congregations with proper schooling and financial assistance.The church also served as the political headquarters for the black community. Elections of bishops and other officers became a serious activity in black communities. |

The Role of Gender in the African American Church

Although men occupied the powerful positions within the church infrastructure,

women played an important role in the black church. Women generally outstripped men in church membership, attendance,

and active participation. Their commitment led many to identify them as the true backbone of any strong church.

"Despite the fact that nominal control and direction are in the hands of the men, women ... contribute a larger

share of the financial and moral support. Church politics is primarily a man's game, but the women wield great

indirect power" (Sernett, African-American Religion in the Twentieth-Century).This opportunity to achieve recognition cannot be under-emphasized. Living in a society in which

social mobility rarely extended beyond the tightly-confined boundaries prescribed by the whites, recongition within

the church spoke volumes. As African American historian Benjamin E. Mays notes, the church helped turn ordinary

members of the African American community into powerful figures: "A truck driver of average or more than ordinary

qualities becomes the chairman of the Deacon Board, while a woman who would be hardly noticed, socially or otherwise,

becomes a leading woman in the missionary society" (Mays, "The

Genius of the Negro Church").

Church Center of Activity In Delta Communities

| Previously a strong source of inspiration in African Americans' lives, the church in the Delta held these segregated communities together. Most major activities in any given community stemmed from the church. "From the very beginning," historian Forrester Washington points out, "the Negro has had to make numerous approximations and substitutions to supply himself with decent recreational opportunities. In both city and country he has made of the Negro church a quasi community center" (Sernett, Promised Land). Religious revivals, held each summer by African American churches, exemplify the role played by churches in strengthening communal ties. |

|

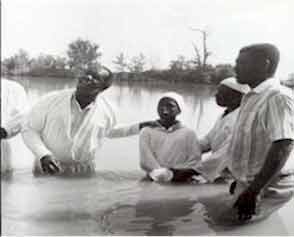

Summer revivals also served to draw in members of the African American community

unaffiliated with the sacred aspects of the church. Churches used revivals

to bring in new members. Ministers and visiting assistants preached up to

three times a day on a variety of topics aimed at bringing "sinners"

to their knees. Frequently, non-members crumbled under the pressure, otherwise

known as "Convicted of his (or her) sins." As Carter G. Woodson

describes the expereince: the person becomes "thoroughly alarmed as to

his lost condition and while in a state of prayer from deliverance from sin,

he falls into a trance, prostrate like a man in dying condition" (Woodson, "Things of the Spirit").

The powerful effect of such a spectacle usually enitces other non-believers

into submission. Woodson adds, "Before the end of the week, practically

all malefactors in the neighborhood, except those ╬hardened in their sins',

are converted" (ibid).

The success of these revivals did not result merely from the preachers' ability

to orate, but moreover from the celebratory and festive nature of summer revivals.

The church provided entertainment as well as feasts unparalleled anywhere else in the black Delta. "Worldly

people not the least interested in the religious effort," historian Milton

Sernett notes, "often attend these meetings to feast and socialize with

friends who are not otherwise brought together during the whole year"

(ibid).

Church Refuge From A Cruel World

| Indeed, churches proved instrumental in the process of socialization and communal development in the Mississippi Delta. The church's status as an inalienable institution, however, stemmed from the spiritual solace and sense of personal independence religion offered African Americans. More than any other southern institution, the church afforded blacks the opportunity to escape from the harsh realities of their external world. Richard Wright, in 12 Million Black Voices, asserted: "It is only when we are within the walls of our churches that we are wholly ourselves, that we keep alive a sense of our personalities in relation to the total world in which we live ... Our churches are where we dip our tired bodies in cool springs of hope, where we retain our wholeness and humanity despite the blows of death from the Bosses of the Buildings" (Sernett, Promised Land). Church services were, amongst most African American congregations, highly emotints. The nature of such expressions only reflected one's personal avenue toward spiritual cleansing. |

|

Churches Often Apathetic to South's Racial Conditions

While serving as an agency for emotional release, the church concurrently acted as an ally in the preservation of the status quo. Rather than inciting its congregation into action, most churches instead encouraged blacks to accept their inferior status. Whether it be through their continuous emphasis on the rewards of the afterlife or their silence on the atrocities occurring daily throughout the region, churches often acted as a negative force in the flourishing migration.

|

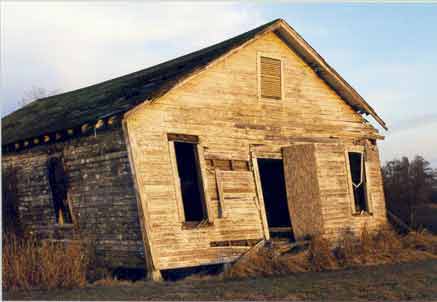

condemned church of "Sonny Boy" Williamson in Delta region of Mississippi |

Numerous factors can be attributed to such a stance. First and foremost, most blacks churches were engaged in a constant struggle to survive. Chronically short on funds yet expected to perform numerous social services, churches were often overwhelmed to the point that issues beyond the congregation possessed diminished significance. Black churches possessed a great degree of autonomy within southern society, but their autonomy often rested on acceptance of the racial caste system. Financially, many churches depended on white benefactors for survival. This "gift" relationship forced many churches to avoid political involvement in exchange for white protection. It must be noted, however, that the great majority of African American churches in the Delta received little or no support from whites. |

NEXT

BACK