Differences Between Northern and Southern Churches

Established South-Side black churches exhibited marked differences from their southern

counterparts. Unlike the overt expressiveness characteristic of Delta churches, Chicago's church services were

restrained. Congregations were expected to follow prescribed procedures rather than respond spontaneously. Ministers

rarely entered the ministry via a "call from God," but were instead college-trained men who possessed

extensive education and wide experience within the church. Delta churches were small and highly personal; in contrast,

most of the established South-Side churches boasted large congregations. Migrants found South-Side churches impersonal,

cold, and alien to their own religious experience.

In such an environment, migrants frequently felt out of place and utterly uninspired. In response to the solemnity

of church services, one migrant commented, "nobody said nothing aloud but there were whispers all over the

place" (Sernett, Promised Land).

Frustrated by the lack of attention she received in her new church, another migrant complained, "The preacher

wouldn't know me, might could call my name in the book but he wouldn't know me otherwise. Why, at home whenever

I didn't come to Sunday School they would always come and see what was the matter" (ibid).

|

Olivet Church on E. 31st in Chicago |

Although many were disenchanted with established black Chicago's religious life, migrants nonetheless flocked to these churches in droves. Olivet claimed 3,900 congregants in 1915; by 1919, they served 8,430 members. In response to such a staggering increase in numbers, many churches moved into new facilities. During the the Great Migration, whites slowly abandoned the South-Side in favor of North-Side suburbs. With their departure, many white churches sold their property to black congregations. Wealthier churches frequently obtained these abandoned churches. The improved facilities, while providing space for the expanded congregations, further distanced the established black churches of the Old Settlers from the religious preferences of most migrants, reinforcing class differences within the South Side black community. |

Some churches compromised their traditional religious practices in order to accommodate their new members. They incorporated gospel choirs, and added new, more vibrant songs to their tradtional church hymns. Educated and theologically-sophisticated ministers livened up their sermons by interjecting "shouts" and encouraging emotional responses from the congregation. Overall, though, migrants still found themselves set apart by their class status, appearance and demeanor. Condescending attitudes toward the migrant predominated upper-class church congregations.

|

A female member of a South-Side Episcopal church commented: Any church that doesn't have the class of people that we like to associate with would be very unpleasant; not that we feel that the other people are not nice but they are too poor to keep up with that kind of life. Sometimes a group of us would go to some small church but they are so backward we feel ashamed of them and we could not be a member of that kind of church. |

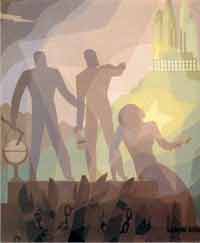

Aaron Douglas, Aspiration 1936 |

In response to such comments, migrants often rejected the "Old Settlers"' churches and formed their own churches that replicated Delta practices. Some southern congregations migrated to Chicago as a group, maintaining not only their customs but also their group identity. The desire to preserve the intimacy and expressiveness of southern church life manifested itself in the numerous small prayer groups (conducted in a migrant's home) and Storefront churches throughout the South-Side.

Storefront Churches: An Attempt to Preserve Southern Religious Tradition

|

Picture of a storefront church |

|

Migrants expressed a variety of reasons for attending such churches. One Storefront preacher commented that many of his members simply could not tolerate the repressiveness of the traditional churches: "The old people want to shout sometimes, because this gives them a chance to express themselves in the way they desire. They feel the spirit and have to give vent to their feelings. In these larger churches, they don't feel as free" (Drake, "Social Classes..."). A member of a storefront congregation appreciated the relaxed and tolerant environment such churches provided: "the people in this church don't pay so much attention to how you are dressed. All they want is that you be a Christian and attend church regularly" (ibid).

Despite the positive and harmless rationale behind such church formations, storefronts drew the scorn of the established African American church community. A member of an upper-class church commented:

I have always dislike the storefront churches because I feel that they are operated and attended by people who represent the most ignorant group. The preachers are some of those who have not learned how to take orders, and that fact alone proves that the person is not a fit leader. Those who form the congregation are people from the South that know religion only as the amount of noise made, ╬shouting', and exhibiting their emotions (Drake, "Social Classes...").

Many derided storefronts as a disgrace to the African American race: "They are demoralizing

to our race.... I think the people of this type are in the first stages of insanity," commented a Presbyterian

pastor (ibid). Storefront preachers often garnered

the brunt of the upper-class scorn. These preachers were, as William Welty notes, "derided for their lack

of formal training and were subjected to accusations including defrauding their flock of money, being agents in

the numbers racket, and of immoral sexual behavior" (Sernett, Promised

Land). A young Presbyterian pastor sarcastically derided a female Storefront preacher,

whose weekly radio program catered to the lower-class. "The white people enjoy her ignorant broadcasting,

because it plays up to their vanity," the minister remarked. "Of course, it is a wonderful way to advertise

the lower elements of her race. The more intellectual people consider it a show; almost a minstrel" (Drake, "Social Classes..."). Despite such criticisms,

storefront churches persisted, their presence a testament to the strength of migrants' southern religious heritage.

Migrants' entrance in the South Side's social structure profoundly affected

the role the nature and function of the church. The Old Settlers saw their restrined approach to religious worship

increasingly undermined by southern relgious practice. Their attempts to adjust, while often minimal at best, underscore

the wider dynamics of this cultural hybridization. Migrants' close connections to their southern religious traditions

led many to attempt to recreate a rural religious atmosphere in the heart of an urban envionment. Exemplified by

storefront churches, such reactions to city life show that migrants, while forced to discard many aspects of southern

life, fought hard to preserve their personal connection to God. More than simply an exodus from the South, the

Great Migration, as seen in the changing face of South-Side church life, instigated a transformation and eventual

aggregation of two radically distinct components of African American culture.