Duality of

Gospel

and the Blues

Every person and object has a twin, which also serves as its opposite. This paradox

was a common belief among the Yoruban people of Africa, and often was depicted as the deity, Eshu-Elegba, known

as both a divine spirit and the Devil. Associated with change, Eshu-Elegba is portrayed as both holy and evil,

and thus symbolizes the crossroads. Elegba, or "owner-of-the-power," also is a messenger, between men

and gods, and among men. He is the African equivalent of Hermes. Moreover, as a messenger and deliverer of current

news among men, he is the epitome of the West African griot, the Irish Bard, and the ultimate informer through

art and spirituality. Eshu-Elegba continues to represent the dual nature and basic principles of African-influenced

religion and culture, even today. Such characteristics are evident in the dualistic natures of gospel and the blues. Despite many differences, both genres provided a sense of

refuge for black musicians.

|

Whereas gospel inspires hope and

a belief in a better afterlife, the blues dwells in the grit and circumstance

of everyday life. As Alan Young notes in Woke Me Up This Morning,

the difference exists in the lyrics. For example, a blues artist wakes

up alone to discover his wife has left him, but a gospel singer wakes

up with God on her side. "Blues"

is the sense of things getting worse while gospel music roots itself

in the faith that things are starting to improve. Ironically, devastation

and crisis also inspire gospel music. According to Charles Haffer, Jr.,

a Mississippian Baptist preacher, "It's what we call a warning

song. When we write about disasters, our object is to warn the unconverted

or the careless or unconcerned Christians" (Lomax,

The Land Where the Blues Began). |

During the 1930s and 1940s, ministers like Haffer used gospel music as

a means for informing the congregation about current news and national disasters. Mirroring the role of the griot

or messenger, Haffer wrote many gospel songs-- "The Sinking of the Titanic," "The Natchez Fire,"

and "The Storm at Tupelo." During World War II, he wrote "A Patriotic Song of the European Conflict:"

If you stop and listen, I'll sing you a song.

About the appoiling disaster, while the war is going on.

I'll tell you how it started, and when it all began,

I'll tell you about the suffering; but I can't tell when it will end . . .

"It was in the month of September 1939, war broke out in Europe,

And made everybody troubled in mind.

Germany invaded Poland, and whipped them in eighteen days

Drove their leaders in exile, and reduced their people to slaves . . .

"Hitler is mean and hateful, violates international law,

That's why we are giving to England everything short of war.

He is s ruthless cold murderer, and that in first degree,

He has conquered most of European land, and now he wants to rule the sea.

"We sang out of our souls," says Mound Bayou's

Debbie Lee, "we sang what we felt . . . we had to steal away because

there was a flood. It was high-water everywhere, and there were songs I can

remember came out of that. Backwater Blues, and another one . . . I can't

remember. Those blues came out of living

conditions."

What Mrs. Lee refers to as "those blues" became a gospel song called "The

1927 Flood," recorded in Chicago by Elders McIntorsh & Edwrads, accompanied by the Sisters Johnson, clapping

and tambourine:

It was in nineteen twenty-seven.

It was an awful time to know.

Through many Delta countries.

God let the waters flow.

The people worked in vain.

But our God wouldn't stop the rain.

Well, He poured down His flood upon the land.

He sent a flood through the land. (Oh, glory.)

And it killed both beast and man.

Oh the people got so wicked.

They couldn't hear God's command.

All prayin', for an appeal.

But the Lord didn't have no deal.

Well, he poured out his flood upon the land.

|

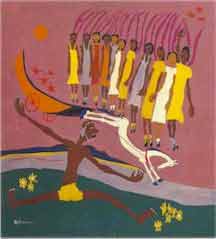

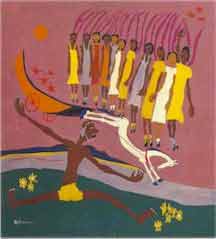

Picture of Gospel song Swing low sweet chariot

|

Often, melodies carry over from blues to gospel,

and vice-versa, with only the lyrics changing. For example, while a gospel song might be punctuated with Amens,

C'mons, Hallelujahs and Oh, Glory's, a blues song would substitute Oh, Lord! with Oh, Baby! In 1927, Reverend Sister

May M. Nelson, signed by Document Records, recorded "The Royal Telephone" with more intensity than an

electric current riding through a wire. She easily could have been a blues singer. Similarly, many black musicians

found themselves tempted by both sides, sacred (gospel) and secular (blues). Charley Patton actually tried to hide

his career as a blues singer from his Baptist church because church people regarded the blues as Devil's Music. |

Congregations condemned blues singers for their wandering and promiscuous lifestyles, inevitably

reflected by the lyrics and song titles, i.e. "It's Too Big, Papa," "Bye Bye Cherry," "Pussy,"

and "She Squeezed My Lemon" (from the album, Copulatin Blues, circa mid-Thirties). Most blues

songs dealt with everything from bootleg whiskey to gritty every day affairs, money problems and cheating spouses.

A devout Christian, Debbie Lee defends the blues:

I like it. I don't think it's the Devil's music. Something about them blues tells

a story. They might be whiskey drinking and socializing at the juke joints, but they are closer in the juke joint

than church, sometimes. They don't worry about germs . . . they hold up a bottle to someone else's mouth . . .

someone falls down, they pick him up again. In the church, they like to hold you down, sometimes. We all sin, come

short of the glory.

NEXT [CREDITS]

BACK

.