The Role of South Side Churches During the Migration

Archibald J. Motley c. 1925

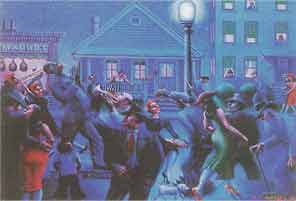

Gettin' Religion

| The Rush

to Accomodate: The Role of South Side Churches During the Migration |

Archibald J. Motley c. 1925 Gettin' Religion |

The Great Migration forced the established African American community in Chicago to make major adjustments and accommodations. Historically, black churches had, like their counterparts in the South, resisted any involvement in social issues. The arrival of hundreds of thousands of migrants, however, simply could not be ignored; churches, being African Americans' richest and most influential institutions, were quickly called to action in the effort to help migrants properly adjust themselves to life in Chicago.Established Northern Churches Called To Action

Grace Presbyterian Chruch in Chicago

African Americans already living in Chicago (commonly referred to as the "Old Settlers") were aware of the implications the Great Migration. The "Old Settlers" strove to establish respect from whites and a sense of equality within the city's socioeconomic system. With the arrival of southern blacks, most of whom unfamiliar to urban mores, the "Old Settlers" feared that the progress they had achieved would be dashed. All whites, Old Settlers feared, would equate all blacks with these rural and uneducated migrants. Moreover, the "Old Settlers" realized the enormous strains placed on many of the migrants who, having fled the Delta, arrived in Chicago lacking proper accommodations or direction in the achievement of personal stability. From the migration's outset, Northern churches bore the brunt of the responsibility for achieving such aims. In 1919, the African American ministerial publication Journal and Guide levied a plea to the Northern African American religious community:

There has been no period in the history of Afro Americans when our great church organizations needed more than now the services of strong and capable men. These are perilous times, and unless signs fail, there are critical times ahead, and we need as bishops, as preachers, and as leaders in every department of our racial activities the strongest men that we can summon to these places of leadership (Sernett, Promised Land).

Northerners were especially wary of the enticements urban life offered. In the Delta, the church was the center of social life. Chicago, on the other hand, provided numerous outlets for entertainment, many of them deemed by the ministry as deviant and potentially destructive. African American social activist Richard Wright, Jr. emphasized the importance the church played in welcoming migrants to Chicago: "Get these Negroes in your churches; make them welcome; don't turn your nose and let the saloon man and the gambler do all the welcoming. Help them buy homes, encourage them to send for their families and to put their children in school" (Sernett, Promised Land).

Churches Assumed Key Role in Helping Migrants Adjust to Chicago

The Olivet Baptist Church, located on the South-Side of Chicago, assumed a major role in the process of aiding migrants. The Rev. Lacey Kirk Williams sent members of the church to the Chicago terminal to meet incoming trains. Church members greeted migrants and immediately directed them to places of assistance. Olivet quickly transformed itself into a social service center for migrants, providing them with food and clothing, while assisting them in the obtainment of housing and employment. They also hosted a wide variety of social, educational, and recreational activities, and soon gained a reputation throughout the South "as an oasis of mercy in the urban desert" (Sernett, Promised Land).

Other black Chicago churches also addressed the practical issues facing migrants. Familiarizing migrants with factory work proved most urgent throughout such discussions. The AME Church, at its General Conference in 1920, appointed a labor commission whose job it was to work towards providing migrants "a wider door of opportunity" through education. As the leaders of the conference point out, "The Twentieth Century industrial plant cannot be manned by men not yet advanced from the Eighteenth Century method of industry" (Sutherland, "An Analysis of Negro Churches in Chicago"). The commission sought to instruct migrants on the proper techniques used in finding employment opportunities, how to conduct themselves before white bosses, and how to adjust to the increased demands of industrial labor.

In adopting such secular goals, churches fulfilled a practical aim, as well. For within this confusing urban environment, migrants sought out institutions that could prove influential in helping them meet immediate concerns. The minister who could deliver them jobs enhanced his chances of recruiting new members of the congregation. Furthermore, Chicago churches, having to compete with secular institutions, needed to make such adjustments so as to retain their sense of authority within the expanding community. A Chicago preacher exhibited his acute awareness of the adjustments enforced upon his church:Saving souls is not enough; we need a more practical religion. We are now emphasizing religious education, social activities, and even recreational opportunities. We must build the body as well as the mind. These activities can be carried on in the church under more wholesome influence than if the [migrant] were left to discover his own means of entertainment (Sutherland, "An Analysis of Negro Churches in Chicago").

As this comment illustrates, African-American churches quickly realized that they needed to ardently compete to gain the loyalty of highly-impressionable migrants. As the Chicago Commission on Race Relations in 1919 observed, "The field wholly occupied in the South by the church is shared in the North by the labor union, the social club, lectures, and political and other organizations" (Sernett, Promised Land). No longer guided by an "all encompassing" institution, migrants soon discovered that city life offered many secular-based outlets for prestige, entertainment, and emotional fulfillment. Accordingly, churches scrambled to answer the pressing demands of its new arrivals, if merely to ensure their social significance.