The status of the church in southern African American culture made preachers de

facto leaders of the community. In the wake of the Great Migration, it was their reaction which exemplified the

precarious state of "autonomy" enjoyed by churches. Moreover, the expectations placed upon the preacher

in the lives of blacks in the Delta underscores the nature and function of religion in these rural communities.

General Characteristics of the Southern Minister

Rather than a man well-versed in Biblical and scholarly interpretation, African American congregations often preferred a minister effective in eliciting an emotional response from the audience. Ministers were not expected to consciously aspire to the ministry, but instead must first "see the light and hear the call." The minister was "an inspired man" who transcended secular understanding. Many rural preachers possessed little or no formal education. African American historian Carter Woodson critically commented, "the ministry of the Negro church must be recruited from the mentally undeveloped members who have any amount of spirit but little understanding" (Sernett, Af.-Am. Religion in the 20th Cent.). Some denominations attempted to combat this tendency. The Methodist church utilized its strong centralized authority to require educational standards. The Baptist church, lacking institutional authority to control its churches, proved unable to insist on an educated ministry.

|

|

Rather than a liability, many ministers used their lack of education as further proof of their sincere connection to God. Such tactics often garnered criticism from fellow members of the community. Cohn remarks, "They know the weaknesses and credulousness of their congregations, and how to play upon them for their own material benefit" (Cohn, Where I Was Born and Raised). Indeed, aside from the ability to inspire the congregation on Sunday, successful ministers often possessed a great degree of sex appeal. "Lusty manhood" usually ensured the minister that he would be "well fed, well clothed, well housed, and well paid" (ibid). When asked why he attained such a degree of popularity amongst his congregation, one minister responded: "Cap'n, a nigger preacher ain't got to have but two thingsöa bass voice an' make de bedsprings moan" (ibid). |

Ministers Often Adopted Ambiguous Stance on Migration Question

In the years of Great Migration, black ministers increasingly became targets of criticism amid the growing restlessness of the Delta's African Americans. Many ministers exhibited an ambivalence to secular concerns. A Delta minister expressed an opinion shared by most other church leaders: "Others calling themselves ministers are bringing worldly things into the church; but as far as for me and my house we will serve the Lord" (Sernett, "Af.-Am. Religion..."). As debasement of blacks by the white ruling class grew in scale and severity, many began calling for ministers to discard such notions and begin addressing the moral and ethical questions surrounding the caste system and blacks' proper response. African American historian Ralph Bunche argued that the southern minister was ineffective in improving the conditions of his congregation:

The Negro preachers ... as a whole have avoided social questions. They have preached thunder and lightning, fire and brimstone, and Moses out of the bullrushes, but about the economic and political exploitation of the Negro ... they have remained silent. The congregations have looked at them with eyes of suffering and Negro preachers have turned from them and preached the virtues of Canaan (Frazier, Negro Church in America).

The Minister's Dilemma

The Great Migration undermined the authority of the minister. Faced with the choice of either alienating their congregation through denouncing the Migration or drawing the ire of whites by encouraging this mass exodus of labor, ministers often chose to remain silent. Some practiced subtle techniques, such as espousing on the evils of city life. Booker T. Washington, the foremost proponent of acceptance of the South's depreaved racial conditions, argued, "In rural districts, the Negro, all things considered, is at his best in body, mind and soul. In the city he is usually at his worst. Plainly one of the duties of the church is to help keep the Negro where he has the best chance" (Sernett, Promised Land).

|

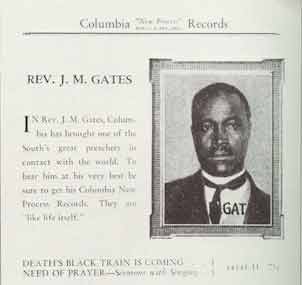

Reverend Gates: One of the most successful recorded ministers. Nothing But the Blues by Lawrence Cohn |

In response to the Migration, other ministers seemed convinced that race relations were improving. "There are many signs of hope and promise in the skies for better things in the South for us as Negroes," the Rev. J.H. Eason argued. "Be manly and patient. Don't move too fast and in such large numbers. Several things must come up to us as a race before we can enjoy many rights and blessings that we desire. It matters not where you go. Look well before you jump" (Sernett, Promised Land). Still, black ministers found it increasingly difficult to ignore the terrible conditions of African Americans in the South. In response to Bishop Benjamin F. Lee's denouncement of the migration, migration advocate W.A. McCloud wrote, "I wander did the Bishop read of Lynching of that good Citizens of Abbeville, who was worth $20.00 and hundred of outher good men who has been hung up by thes Midnight Mobes. And yeat the bishop Adise them to stay in a cuntry like that? It seems to me that all the bishop wants is for his church to Live and the rest may die" (Sernett, Promised Land). |

During the Migration black ministers in the Delta saw themselves bombarded from all sides. Seemingly any possible interpretation of the Migration placed the preacher in a precarious state. African American scholar Emmett Scott explained:

For the pastors of churches it was a most trying ordeal. They must watch their congregations melt away and could say nothing. If they spoke in favor of the movement, they were in danger of a clash with the authorities. If they discouraged it, they were accused of being brought up to hold Negroes in bondage. If the pastor attempted to persuade negroes to stay, his congregation and his collection would be cut down and in some cases his resignation demanded (Frazier, Negro Church...)

"A Leaderless Movement"

The church's inability to effectively address the Migration question profoundly

affected the nature of the Great Migration. Being as minsters were often the leading figures within a given community,

blacks who chose to migrate did so on their own without seeking religious-oriented advice and direction. Many did

not even inform their minister of their plans to migrate to Chicago. They simply left without notice. Ministers

arrived at Sunday service only to find fewer members of his congregation. The Great Migration thus represented

a truly unique movement, for it was not instigated nor guided by the influential members of African American communities.

Instead, migrants relied upon their own judgment to abandon the Delta. African American scholar and social commentator

W.E.B. DuBois commented: "The wave of economic distress and social unrest has pushed past the conservative

advice of the Negro preacher, teacher and professional man, and the colored laborers and artisans have determined

to find a way for themselves" (Sernett, Promised Land).

By avoiding the imperative of migration, African American churches lost much of their membership. Once in the North,

Deltans reformed churches, but many of these were Storefront churches in which the congregation played as important

a role in ther service as the minister. A result of numerous factors, the Great Migration spelled the end of ministers'

unquestioned dominance over the political and social realm of the African American community.